Introduction

Artificial intelligence has become the defining technological theme of the current decade. From large language models to intelligent automation, AI is revolutionising how even the most basic tasks are performed in the workplace. This rapid transformation has, in turn, triggered heavy investment from sovereign wealth funds to private equity firms, all scrambling to secure a piece of the rapidly growing AI market. According to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development[1], the global AI market is projected to grow from approximately $189 billion in 2023 to around $4.8 trillion by 2033, positioning AI as the dominant technology of the next decade.

To facilitate this unprecedented growth, the companies that form the backbone of the AI economy, including hyperscale cloud operators, telecommunications firms and data-centre developers, are expanding critical digital infrastructure at extraordinary speed and scale to meet rising demand. At the centre of this emerging AI economy are data centres, which host the computational power and storage capacity required to train, run and deploy these AI tools.

Consequentially, financial news organisations and investment firms continuously mention aggressive compound annual growth rates for AI and AI-adjacent[2] firms, reinforced by a stream of multi-billion-dollar capital expenditure programmes from firms such as Nvidia, Google and others.

However, the current narrative rests on a critical assumption: that the supply chains that underpin data centre construction can scale smoothly, quickly, and proportionally to demand. This assumption is critical to the AI economy, but is it a safe assumption to hold?

The supply side of the data-centre economy is far more complex than many would assume. Data centres are not just prefabricated assets that can be easily manufactured. They are large-scale, physical, power-intensive systems that rely on a tightly interwoven set of inputs: land, power generation, grid interconnection, cooling systems, water and wastewater infrastructure, specialised electrical and mechanical equipment, physical security, fibre connectivity, and a skilled construction and operations workforce. Scaling any one of these in isolation is possible but scaling all of them simultaneously at a national scale, and at the pace implied by current market expectations, often involving high double-digit compound annual growth rates in data-centre capacity, is a completely different question. The result is a potential growing disconnect between demand-side expectations and supply-side feasibility.

This paper argues that data-centre growth forecasts systematically understate the friction in the supply chain. Much like assuming that more cars can be produced simply because consumers want them, without checking whether steel, factories, skilled labour, or logistics capacity exist, many AI-driven capacity projections implicitly assume that bottlenecks can be easily overcome. In practice, constraints are emerging across multiple layers of the ecosystem, from power availability and grid interconnection queues to construction timelines and labour force availability.

This paper focuses on the U.S. market over the next three to five years and challenges prevailing assumptions around data centre scalability. Drawing on industry forecasts, proprietary modelling, and infrastructure-level evidence, we isolate where current expectations break down, and why supply-side realities matter more than ever for investors, operators, and policymakers navigating the AI infrastructure cycle.

Factors of Production

Data-centre Capacity is often discussed as if it were a scalable abstract asset, measured in square footage or megawatt capacity. However, capacity relies on a wide variety of component systems that all work together, such as regulatory, physical and operational inputs. Each system has its own needs and requirements, and if any one of those is interrupted or delayed, it can reduce or even halt capacity from being further developed or deployed. Understanding how these processes work together is essential for determining whether new data-centre projects can be constructed and operated at scale. For a data centre to be competitive, there must be a synchronisation of various factors, for example: high-capacity connections, affordable power and land, amongst others.

Beyond these considerations, regulatory factors also play an important role. In a federalised system such as the United States, planning and permitting requirements vary significantly across states and local jurisdictions[3], creating wide disparities in approval timelines, compliance burdens, and environmental standards.

However, the most crucial operating constraint is power generation. Firstly, if there is not sufficient power in a grid for a data centre to be constructed, the data centre will not be able to physically operate. Power supply must also be consistent in order to make sure that operations within the data centre can run without compromising performance or data. Secondly, there must be sufficient excess capacity in an energy generation district to ensure that electricity costs (the highest operating cost in running a data centre) are kept sufficiently low so that the data centre can be run at a competitive price, not only at the point of initial operation but on a sustained, long-term basis. If power costs rise unexpectedly after a facility is built, operating economics can be materially impaired, potentially rendering a site uncompetitive.

While data centre development depends on a wide range of inputs, these constraints do not bind equally.

In practice, supply growth is determined by the slowest and least substitutable component rather than by the average conditions across the system. Among all factors of production, power availability and grid connectivity represent the dominant binding constraint. Unlike capital, land, or equipment, large-scale, reliable power cannot readily be accelerated through higher spending alone and is governed by multi-year generation, transmission, and interconnection timelines that are largely fixed. Other constraints such as labour availability, permitting complexity, and site selection primarily act as cost and timing amplifiers. These constraints can be partially mitigated through higher prices, prefabrication, or geographic flexibility, but only within narrow limits. Critically, none of these mitigations resolve the underlying dependency on firm power delivery. As a result, the increase in data-centre capacity is capped by the pace at which power infrastructure can be expanded and connected, regardless of demand intensity or capital availability.

Timeline of Factors

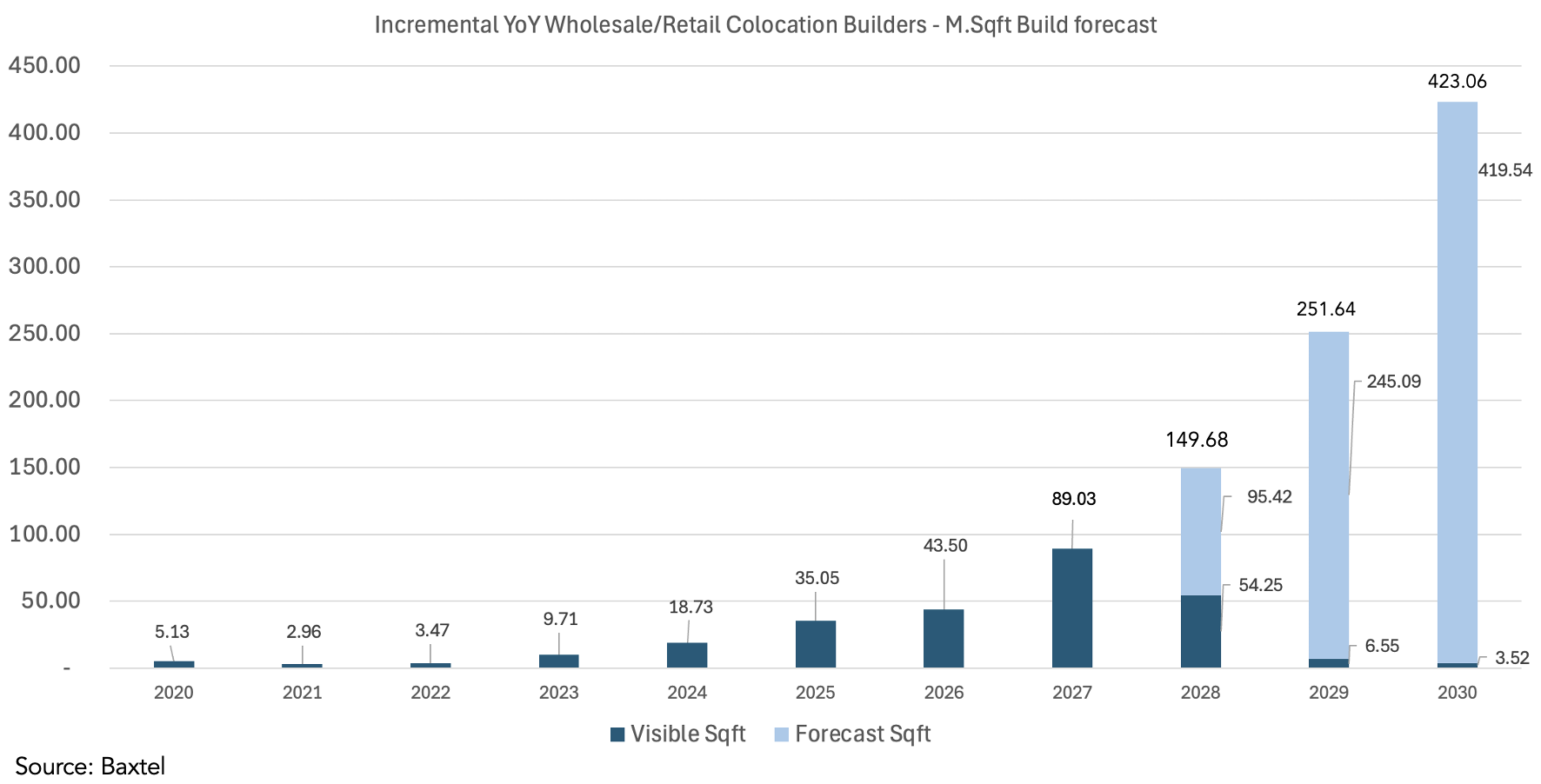

To establish how feasible the current market growth estimates are, we must first identify those forecasts. Using Baxtel, a specialist market intelligence firm focusing on data centres, and 4MC Partners analysis, Figure 1 summarises the implied year-on-year build-out trajectory for wholesale and retail colocation capacity.

Figure 1

Figure 1 illustrates year-on-year incremental increases in data-centre square footage that has been built or is planned to be built by colocation data-centre operators such as Digital Realty, QTS, Vantage and others. The dark blue segments represent visible capacity, i.e. projects that are already under construction or firmly committed, and therefore highly likely to be constructed and delivered.

Figure 1 illustrates year-on-year incremental increases in data-centre square footage that has been built or is planned to be built by colocation data-centre operators such as Digital Realty, QTS, Vantage and others. The dark blue segments represent visible capacity, i.e. projects that are already under construction or firmly committed, and therefore highly likely to be constructed and delivered.

By contrast, the light blue segments represent forecasted data centre build based on the compound annual growth rate seen over the period 2024 to 2027 (with data centres typically taking 18–36 months to deliver, projects for 2027 delivery are already underway). In other words, if the trajectory of the past few years were to continue, we would expect to see the expansion in data-centre capacity rise from 89M Sqft in 2027 to over 423M Sqft in 2030. As such, to be able to deliver such capacity at the projected growth rate is inherently more uncertain and dependent on the supply of the aforementioned input factors.

The analysis in this section focuses specifically on this forecasted component, as it represents the incremental supply that must materialise to meet expected demand growth, and therefore this constitutes the most critical and potentially constraining assumption underlying long-term capacity

For the forecast capacity shown in the light-blue segments to be realised, the underlying factors of production must scale at comparable rates. Rapid increases in data centre square footage implicitly require congruent growth in power generation, grid interconnections, construction throughput, and supporting infrastructure within a corresponding delivery window. However, the timelines governing these inputs do not align with the pace implied by market projections. Power infrastructure expansion typically operates on multi-year cycles, grid interconnection queues are already congested in many key regions[4], and construction capacity is constrained by both labour availability[5] and sequencing limitations[6]. As a result, the compound annual growth rates embedded in long-term capacity forecasts are inconsistent with the observable growth rates and delivery timelines of the critical inputs required to support them.

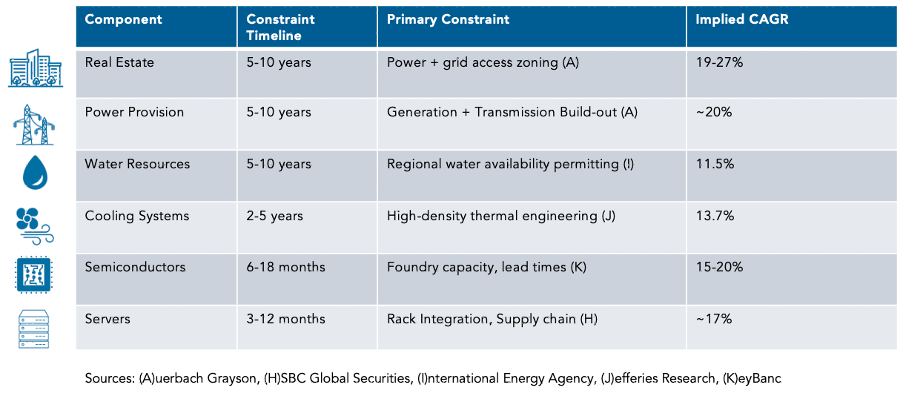

The critical question is whether the compound annual growth rates of the underlying components are congruent with the growth implied by market forecasts, particularly over the 2028–2030 period where visibility is significantly reduced due to a large share of projected capacity in the colocation data-centre segment remains uncontracted, unconfirmed, and unexecuted. This can be assessed by examining leading indicators across the key factors of production that determine data-centre capacity delivery. If these inputs cannot scale at rates consistent with the projected increase in data centre square footage, then the forecasted capacity cannot be realised. In this framework, divergence between component-level growth and market consensus capacity projections provides a clear signal that consensus overestimates the amount of deliverable supply. Table 1 presents the key component-level growth signals and delivery constraints that inform whether projected data-centre capacity can be realised over the 2028–2030 period.

Table 1

Using these component-level constraints, 4MC Partners’ internal analysis estimates a sustainable compound annual growth rate for colocation data-centre capacity of approximately 16–18%. This range is broadly aligned with external estimates published by Goldman Sachs Research, which indicate an implied growth rate of approximately 17%[7] over the mid-to-late 2020s.

Additionally, one crucial aspect of data centre construction that is harder to quantify is the US labour force. The US is expected to have a reduction in the current construction labour force of about 40% by 2031[8]. This will result in increasing costs of hiring construction labour but also delays in construction times. Moreover, U.S. industry research further indicates that labour shortages, alongside power and equipment constraints, are contributing to extended preconstruction phases. Requirements related to substations, transformer procurement, and transmission upgrades can materially delay projects before ground is broken, with power-related preconstruction and grid enablement adding one to four years to delivery timelines in some markets and extending total project schedules by multiple years[9].

Moreover, power infrastructure cycles have a period of typically five years or more from planning to being operational[10].This conflicts with data-centre delivery timelines of two to three years. As a result, shortages in available power can delay projects or push development away from ideal locations toward regions with greater headroom in power supply, trading efficiency in other aspects. This dynamic is also contributing to the concentration of new data-centre construction in a narrower set of U.S. regions. To mitigate these constraints, some operators are exploring behind-the-meter solutions, in effect developing on-site or vertically integrated power supply to secure near-term capacity. This can be observed in large-scale initiatives such as Stargate LLC[11] and in hyperscalers’ pursuit of non-traditional power sources, including Google’s agreements with advanced nuclear developers[12].

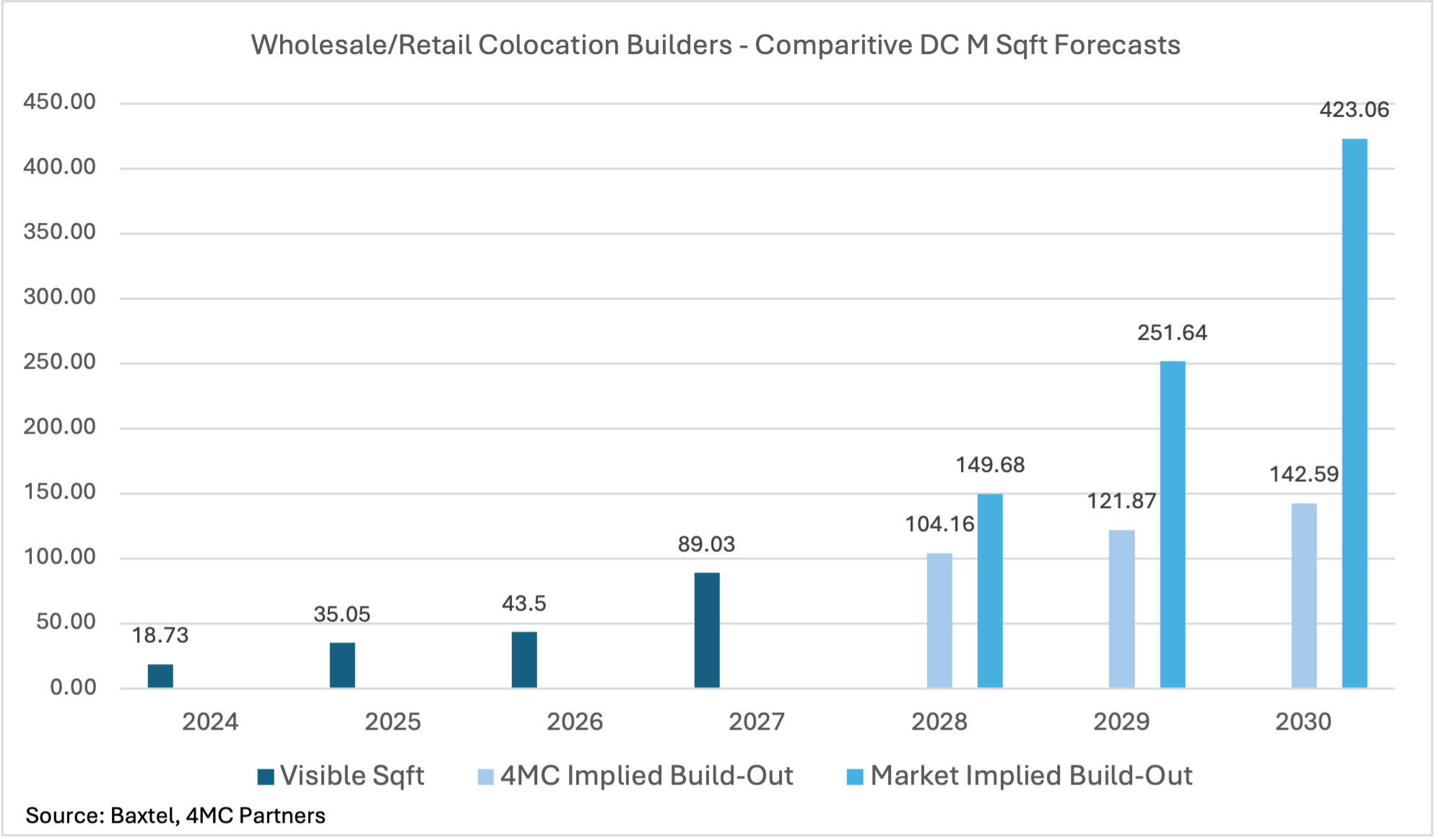

With these facts in mind, applying the 4MC Partner’s view of an annual growth rate of 17%, the resulting forecasted increase in colocation data-centre square footage is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2

Impact of Mismatch

The most obvious effect of a more reasonable compound annual growth rate of 17%, compared to 68%, is that overall expansion of data-centre capacity will be slower than some market estimates imply. While not all data-centre space is intended for or capable of supporting high-density AI workloads, the tighter supply across the sector will still constrain the availability of suitable infrastructure for AI deployment. The question then becomes, how will the market adapt to this more constrained growth?

Firstly, the potentially available data-centre capacity will be in extremely high demand. This will result in computing companies that have the institutional influence and the means, commonly known as hyperscalers (such as Meta, Amazon, Google) likely acquiring access to said limited resources ahead of other smaller or newer operators, often referred to as neoclouds. This will in turn squeeze neoclouds, preventing them from having the high-performance and computing capacity required to either sell or develop their own AI applications. Supply will be directed to those with the most resources and capability.

Secondly, data centres will be concentrated in areas where already existing power and water infrastructure has sufficient headroom to support incremental increases in compute load without the need for new generation or major supporting infrastructure upgrades. This allows for lower marginal infrastructure costs and faster construction timelines. As a result, a data-centre operator may be willing to be inconvenienced when it comes to location in exchange for faster access to firm utility capacity, lower operating costs and increased certainty around construction delivery.

Thirdly, constrained compute capacity may result in deferred demand. Projects dependent on high-density infrastructure face longer deployment timelines, limiting the pace at which productivity gains and revenue opportunities can be realised. Moreover, this means that enterprise AI deployments, large-scale model training, and capacity-intensive workloads may be delayed, hindering revenue recognition and slowing the realisation of increases in expected efficiency. As a result, current consensus assumptions around the near-term economic impact of AI become overstated.

For investors, this mismatch implies that data centre growth and by extension AI monetisation will be slower and more uneven than widely projected. Companies priced on aggressive capacity expansion assumptions may face earnings disappointments, while speculative infrastructure investments carry heightened execution and financing risk[13]. In this environment, supply becomes the governing variable for AI-driven growth.

Summary

Artificial intelligence has rapidly become the defining technological theme of the decade, driving extraordinary expectations for growth across AI and AI-related industries. These expectations have translated into aggressive data-centre expansion forecasts, reinforced by continual media coverage and large capital expenditure commitments from major technology firms. However, much of this narrative assumes that the physical supply chains underpinning data-centre development can scale smoothly and proportionally with demand.

This paper challenges that assumption.

Data centres are not abstract digital assets that can simply be expanded on paper. Their development depends on a tightly interwoven set of real-world inputs, most critically reliable power supply, construction capacity and labour availability. Each of these operates on long, inflexible timelines that do not align with the rapid growth rates implied by current market projections. In particular, power infrastructure requires multi-year planning and deployment cycles, while structural declines in the U.S. construction labour force are expected to slow build times and increase delivery risk.

Using U.S. market data, industry intelligence and 4MC Partners analysis, this paper demonstrates that consensus forecasts significantly overstate the volume of data-centre capacity that can realistically be delivered over the next three to five years. The gap between demand expectations and supply feasibility is widening, creating a structural bottleneck in the AI infrastructure cycle.

The implications are significant. Scarce capacity will be concentrated among hyperscale operators, development will increasingly shift toward regions with excess power availability, and AI deployment timelines are likely to extend beyond current expectations. For investors and operators alike, supply rather than demand will ultimately dictate the pace and distribution of AI-driven growth.

Notes and Sources

[1] UN Trade and Development (UNCTAD), AI market projected to hit $4.8 trillion by 2033, April 7, 2025. https://unctad.org/news/ai-market-projected-hit-48-trillion-2033-emerging-dominant-frontier-technology

[2] For the purposes of this paper, “AI-adjacent” refers to firms whose primary revenues are not derived from the direct development or sale of artificial intelligence models or applications, but whose products and services are critical enablers of AI workloads, including compute hardware, hyperscale cloud services, data centre infrastructure, networking equipment, and power and cooling systems.

[3] Lawson, A., Offutt, M., Parfomak, P., & Zhu, L., Data Center Energy Infrastructure: Federal Permit Requirements, Congressional Research Service, December 12, 2025.

https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R48762

[4] Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Queued Up: Characteristics of Power Plants Seeking Transmission Interconnection (2025 Edition), Energy Markets & Planning, 2025. Available at: https://emp.lbl.gov/queues

[5] Associated General Contractors of America & Sage (2026). 2026 Construction Hiring and Business Outlook.

https://www.agc.org/sites/default/files/users/user21902/2026%20Construction%20Hiring%20and%20Business%20Outlook%20Report_Final2.pdf

[6] CBRE Research (2023). High Demand, Power Availability Delays Lead to Record Data Center Construction.

https://www.cbre.com/insights/briefs/high-demand-power-availability-delays-lead-to-record-data-center-construction

[7] Goldman Sachs Research. How AI Is Transforming Data Centers and Ramping Up Power Demand. August 29, 2025. https://www.goldmansachs.com/insights/articles/how-ai-is-transforming-data-centers-and-ramping-up-power-demand

[8] National Center for Construction Education and Research (NCCER). How Apprenticeships Empower Adult Learners and Bridge the Construction Workforce Gap. April 30, 2025. https://www.nccer.org/newsroom/how-apprenticeships-empower-adult-learners-and-bridge-the-construction-workforce-gap/

[9] CBRE Research, High demand, power availability delays lead to record data center construction, September 14, 2023.

https://www.cbre.com/insights/briefs/high-demand-power-availability-delays-lead-to-record-data-center-construction

[10] Joseph, R., Manderlink, N., Gorman, W., Wiser, R., Joachim, S., Mulvaney Kemp, J., et al., Queued Up: 2024 Edition — Characteristics of Power Plants Seeking Transmission Interconnection As of the End of 2023, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, 2024.

[11] Reuters, OpenAI unveils plan to keep data-center energy costs in check, January 21, 2026.

https://www.reuters.com/sustainability/society-equity/openai-unveils-plan-keep-data-center-energy-costs-check-2026-01-21/

[12] Silva, J. d., Google to use nuclear power for AI data centres, BBC News, October 15, 2024.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/c748gn94k95o

[13] Ford, B., Oracle delays some data center projects for OpenAI to 2028, Bloomberg, December 12, 2025.

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2025-12-12/some-oracle-data-centers-for-openai-delayed-to-2028-from-2027

Baxtel.com, Data-centre source information provider, www.baxtel.com